Interview with American Cowboy Poet Dale E. Page.

TB: Welcome, Dale. When I first met you and read your poems, I became instantly fascinated with you and your work. I also learned, through an insightful article by Tom Mayo, that the romance of Cowboy Poetry has often been unfairly hounded by disparaging attitudes by the uninformed. Could you please tell our reading audience, What is, and isn’t, Cowboy Poetry?

you and your work. I also learned, through an insightful article by Tom Mayo, that the romance of Cowboy Poetry has often been unfairly hounded by disparaging attitudes by the uninformed. Could you please tell our reading audience, What is, and isn’t, Cowboy Poetry?

DEP: For me, cowboy poetry is the portraying of the American cowboy who raises cattle and uses horses to do it. Despite modern inventions and technology, it still takes a horse to do a lot of the work with cattle. We might have the luxury of trailering our horses to the job site if it’s too far, but in the end, it’s the horse that works the cattle. There’s plenty around a ranch that gets done without a horse, but without a horse, there’s no cowboy. Cowboy poetry has its roots in Celtic music and the folk tales brought to America by mostly British ancestors. While there are those who dispute whether poetry has to have rhyme or meter, the overwhelming number of cowboy poetry has both. Cowboy poetry ISN’T a celebration of drunkenness, infidelity, or criminal behavior. The best poetry is a celebration of a lifestyle which makes some men and women forego an easier life on order to watch the world from a horse’s back.

TB: To set the mood for our readers, we have an audio clip of you reading one of your poems. Could you please tell us the title and give a quick background of the piece?

DEP: This poem was inspired by an event in which I took part. We were riding Benson Canyon in southern New Mexico when a child’s horse began a bucking fit. Thankfully, the child was saved from potentially serious injury or death. I patterned the hero of the poem after a boy from my high school class, who was picked on for his small size. Years later, he saved a life by his quick thinking and fast reflexes. I call this poem In Memory of Shorty O’Hare.

In Memory of Shorty O’Hare

TB: Please describe your ideal surroundings or conditions for writing—including the poem we just heard. And, considering your subject matter, does your environment influence your writing?

DEP: Solitude and silence are the factors which make it easiest for me to write. I’ve done some of my best verses under a clear night sky at high altitudes. I really need to tune out the world and get into the story. After many years in New Mexico, we no longer live in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Living in the Midwest makes it even more difficult for me to tune out the present and go back in time. Autumn trips to the Rockies for horseback trips and cowboy poetry gatherings really rejuvenate my creative spirit.

TB: When and why did you decide to start writing?

DEP: I remember writing my first “theme” in seventh grade English class. I was hooked immediately on the idea of inventing characters and making the story come out the way I wanted.

TB: You have a very colorful background. You’ve worked as a horseshoer, a dude wrangler, and a bull rider; you’ve ended up on the movie set of The Cheyenne Social Club; you’ve been published in numerous journals during your career as a USAF pilot; you’ve been named Best Overall Performer at the Oklahoma State University’s Cowboy Poetry and Songs event; and, in 2010 you took home a silver buckle at the 13th annual National Cowboy Poetry Rodeo in the Poet Serious division. Now, as a professional writer, do you have a core philosophy as to why you write; and if so, can you please describe it?

DEP: My poetry is aimed at creating an appropriate atmosphere in which to convey ideas or pass on my account of a particular incident. I generally use my own life experiences for the narrative poems. But many times I’ve taken stories told to me and turned them into poems. The biggest compliment anyone can give me is telling me that he “saw” the scenes in my poem or could “feel” what the characters were experiencing. I want the reader to know my character and the story. I want him to see what I saw and take something with him.

TB: What life experiences have best prepared you for being a poet?

DEP: I’ve owned horses off and on for over 40 years. My first summer out of high school, I worked as a horse wrangler. I started riding bulls that fall in college. For the next three summers, I guided horseback rides into the Santa Fe National Forest. In the 1980’s, I packed myself horseback into the Pecos and Gila Wilderness Areas in New Mexico. Most of my background in poems comes from these kinds of personal experiences.

TB: Not surprisingly, the ‘horse’ is a major symbol throughout your poems. Jenny’s Colt, is a particularly powerful piece. Can you describe your personal connection to horses compared to how it’s used throughout literature as a symbol of power, nobility, or freedom?

DEP: The domestication of the horse was an enormous step in the advent of mankind. From Genghis Khan’s cavalry to the Comanches of North America, horses made some men more powerful than others. In the case of the cowboy, the horse makes it possible for men to control half-wild cattle. They more than earn their keep. They can carry us at least twice as far as we could walk in a day, into country where few people will walk.

My maternal grandfather used horses on his farm in Oklahoma. He had upgraded to machinery before I was born, but my mother remembered the horses they used for pulling implements and putting up hay. The difference in what my grandfather did was that he used the horse for a tool, and not much more. I’m sure Grandpa’s horses were well treated, but they weren’t given the same close care and comforts as my wife and I gave ours. For the cowboy, there was no life without horses. Though machinery has replaced the draft horse in day-to-day farm work, the American cowboy still uses a horse. There are places where machinery just can’t go.

There is a bond between a horseman and his horse which no animal, not even a dog, can match. When I walked away from my last horse, I admit to shedding a few tears. It was like a piece of me was being taken. My old Doc Bar gelding was more than just a ride. He took me as much as 17 miles on mountain trails in one day and never balked. Not once in the years I owned him did he once hurt me or try to. Outside our own species, there’s no other animal that’s as beautiful as a horse.

TB: Do you have any information or opinion on Horse Whisperers?

DEP: I have witnessed folks who seem to be able to think like a horse. They know what he’s going to do in a certain situation and they know what he’s thinking. Most of it has to do with the horse’s being a prey animal. They usually exercise the “fight or flight” principle when something happens to them. The best horse trainers are able to get a horse to see the trainer as a leader and a source of security. These kind of folks don’t fight a horse. They show him how much better it is to do things the man’s way.

TB: Please tell us about your latest work and what genre it falls into.

DEP: I cut a CD of original cowboy poetry in 2009. By the way, don’t confuse “cowboy poetry” with country music. Generally speaking, cowboy poetry focuses on horses instead of pickup trucks, and is more likely to speak of mountain meadows instead of smoky bar rooms. The poems are built around men and women whose lives revolve around the business of cattle and horses.

TB: This becomes evident from reading your work and is described well through the aforementioned epiphanies of Tom Mayo, who also mentions Cowgirl Poetry. In your opinion, are there any defining characteristics between Cowgirl and Cowboy Poetry?

DEP: I think it’s a case of viewpoint and not of gender. On a family ranch, it’s quite possible that a woman does the work of a hired hand. She’s also a wife and maybe a mother. So she not only does what her husband does, she’s also tasked with making a home for her family. Her poems might reflect the way a woman looks at the world. It’s the same world, but her view is different and her priorities are probably different.

TB: As an aside, I’m curious . . . what kind of music do you listen to?

DEP: My iTunes library is mostly golden oldies from the 50’s and 60’s, or cowboy music. The CD’s I find myself reaching for are likely those of Don Edwards, Dave Stamey, Bill Barwick, Juni Fisher, Susie Knight, or Almeda Terry. They paint pictures of times when men and women lived harder lives, but more easily knew the difference between right and wrong.

TB: What is your best work?

DEP: One of the poems on the CD, Once We Were Kings.

TB: What were your inspirations for writing it?

DEP: It was inspired by returning to a place where I worked over 40 years ago. As I stood there in the corral at the horse barn, I compared my life now to what it had been since that 18-year-old boy bunked in a corner of that barn. This poem, which was a runner-up in the Lariat Laureate contest of the Center for Western and Cowboy Poetry, has been the most requested for me to recite. It celebrates a past to which I can never return, but wouldn’t have missed for anything. I’ve shared this watershed event at several campfires and recited it as a eulogy for an old saddlemaker friend.

Once We Were Kings

TB: Can you describe your writing process?

DEP: I believe having something of worth to say is the most important part of writing. When I get an idea for a poem, I write it down. After I have time to ruminate on the idea, I might write the first verse. It usually steers the poem in a particular direction. I outline the poem to keep me on track, and nearly always know how it’s going to end before I write it. With the outline in one column of my page, I write the verse beside the outlined idea. I have the meter of the poem written down and every verse adheres to that meter. If my words don’t fit the meter, I substitute another word or change the structure of the sentence until it fits. After the last verse, I let the poem age a little. When I come back to it, I edit, edit, edit. I have never written a poem which has not been changed in some way during the editing. I’m married to my editor, and no one else sees the work until we agree it’s done.

TB: I must commend you on your success, because as I read your poems I feel and hear the rhythm and the beat.

This musical quality also ties into the language. One of the first things you and I discussed was terminology unique to the Cowboy genre. Although the strong imagery and sensory impact of Cowboy poetry makes it comfortably accessible, I did end up hunting down an online cowboy dictionary for the odd clarification of new terms. Two of my favorite terms are coosie and waddy. Could you please explain these, and any other terms, and give some background into the Spanish influence?

DEP: A significant number of cowboys of the southwest have been of Mexican descent. It’s only reasonable that their language would be adopted to some degree. From the Spanish la riata, we have “the lariat.” From el vaquero, we have “the buckaroo.” You’ll find “coosie” in “Once We Were Kings.” That’s a transliteration of cocinero, “the cook.” From caballada, the cavalcade, a cowboy says “cavvy” when he refers to a group of horses.

Like wadding in a muzzleloader rifle, a “waddy” was someone who “filled in” when roundup time found a ranch short on help. Neighboring ranches would send their representative to help out, knowing they’d get some “waddy” in return when they needed help. The word “cowpoke” came about because someone had to prod the half-wild cattle into box cars after a cattle drive to the railhead. That word is pretty much interchangeable with “cowboy” now.

TB: Can you tell us about your any upcoming projects?

DEP: I’m considering revising the book I self-published in 2005. I’ll cull about half of it and add better work I’ve done since. My CD has some good work, including Once We Were Kings, but I’ve written several poems since then which I’d like to record.

TB: Would you like to experiment with a different genre?

DEP: I wrote a novel years ago, but only copied it for friends and family. I prefer the more immediate gratification of writing poetry. I have dozens of ideas and first verses written already, so I have the seeds of poems which will last for years. I’ll just stick with poetry.

TB: Do you consider yourself an artist?

DEP: I am when I’m at my best. The satisfaction of creating a plot, choosing the right words, and making those words rhyme and fit a distinctive meter must be like a painter who knows when a painting is done.

TB: Do you have any writing idiosyncrasies?

DEP: I am obsessed with perfect meter and consider it lazy not to make the words fit it. I avoid slant rhymes as not good enough.

TB: Briefly share your thoughts on traditional publishing vs. indie.

DEP: It’s tough to get back your printing costs when you self-publish, but you’ve got to get the material out there somehow. There is so much competition to be accepted by a publisher, but it will drive you to perfect your craft. I have found being a part of cowboypoetry.com to be extremely helpful to me. My poems are juried before they are posted, and I know I have to do my best work if they’re going to be accepted. This has been much more successful in getting my work noticed than my book and it’s made me a much better poet.

TB: What advice can you share with first-time writers?

DEP: Read, read, read. I’d advise the classics. You’ll be less likely to plagiarize, even subconsciously. Learn your craft. In the case of poetry, study the classics for meter and rhyming patterns. Don’t wait for “inspiration.” Sit down and write. And then edit the heck out of it. If you don’t have something to say, no one will care about it. If you don’t say it correctly and clearly, people probably won’t read it or remember it. Find someone who will tell you the truth and let him read your work. Don’t be defensive about honest criticism. Rewrite it and make it better.

TB: Dale, thank you so much for helping debunk some of the misconceptions around Cowboy Poetry, for sharing some very personal experiences and injecting life into this interview with your audio tracks. My guess is that all our readers will take away a greater interest and respect for Cowboy Poetry. And, to our readers, we will leave you with a final reading of Dale’s poem, Jack’s Cabin, and a brief description of the inspiration for this poem. Thanks again for being with us today.

DEP: Thank you!

This poem marked a pivotal place in my writing, being the first one of mine to be accepted by The Center for Western and Cowboy Poetry. It was written in an elk camp in 2005, beside a fire during a light snow. I was in northern New Mexico, within 10 miles of the location of a cabin in Miranda Park. The first time I saw that park, I vowed I’d trade my retirement fund for it. A small cabin sat at the upper end of the meadow, rimmed with aspen trees, at the base of Baldy Peak. I reckoned it was one of the most beautiful places I’ve seen. As I sat in camp remembering the cabin at Miranda, I wondered if it would be so beautiful with no one to share it. Jack’s Cabin is the answer to that question.

Jack’s Cabin

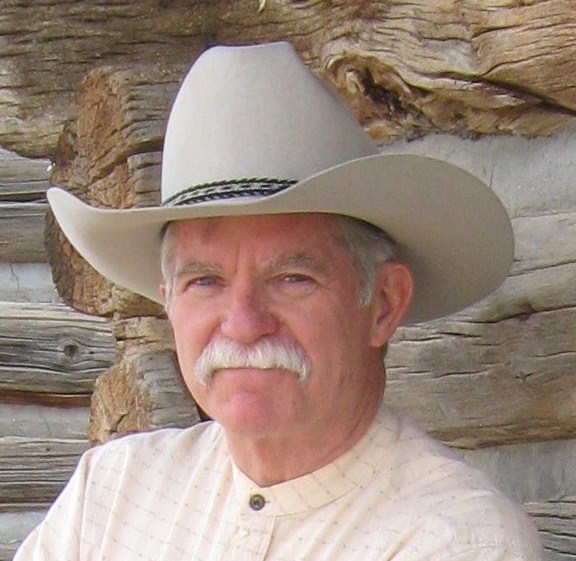

About Dale E. Page

Dale E. Page was born and raised in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. While attending Oklahoma

State University, he worked as a horseshoer, dude wrangler, bull rider, and on the movie set of “The Cheyenne Social Club.” He combined his formal training in English with his horseback experiences in the wilderness areas of New Mexico and began writing cowboy poetry in 1975.

In 2008, he was named Best Performer at the Oklahoma State University library‘s Cowboy Poetry and Songs event. That same year, he was a runner-up in the National Lariat Laureate contest of the Center for Western and Cowboy Poetry. He won First Place in serious poetry, Rising Star Division, at the National Cowboy Poetry Rodeo in 2010.

Page’s A Fork in the Trail, a book of collected poems, was published in 2005. His CD, “The Trail to Miranda Park,” was released in 2009. He has performed at trail rides, campfires, charity events, private parties, church classes, cowboy church services, Friends of the Library, public school classes, and the Indiana State Museum.

Web Site: Contains information to purchase books and CD’s.

Thanks to Eddy Arnold for the use of his track Cattle Call.